The Age of the Canaries

By Mike Hood

It didn’t take long for the birds to seize power.

At first, they tolerated the bright yellow punctuation marks in the dusty sentence of frontier life. But after a soldier tripped over birdseed and accidentally bayoneted the mayor’s hat, a full-blown crisis erupted.

The settlers gathered for an emergency town meeting to discuss irrigation but were drowned out by a mob of canaries. Every time someone spoke against them, the birds swooped down and stole their wig, crucifix, or dignity.

Thus, was passed the first municipal ordinance of San Antonio:

The Sacred Protection of the Canaries Act of 1731.

Any harm done to a canary would be punishable by public humiliation, a small fine, and an essay of repentance in rhyme. The birds were declared “citizens in good standing,” entitled to free roosting and unlimited seed.

From then on, city council meetings had to be shouted over a chorus of canary chirps. The mayor, Don Bartolomé Pérez de las Feathers (a nickname he detested), began each session by addressing both “the human populace and our esteemed avian constituency.”

When the Spanish governor in Mexico City read the report, he assumed it was satire. But when a royal envoy visited months later, he found thousands of yellow birds perched in the rafters, presiding like tiny, holy bureaucrats.

The envoy objected.

A canary immediately dropped something unholy into his cup of chocolate.

He signed the recognition papers before sunset.

San Antonio thrived under its human-bird coalition. Settlers built homes and canals; canaries provided civic morale, pest control, and the occasional celestial soundtrack. When a new priest tried to outlaw their singing during Mass, the birds perched on the altar and performed Ave Maria so beautifully he burst into tears and changed his name to Ignacio Featherlight.

By 1745, the city’s unofficial motto was: San Antonio: Founded by Faith, Sustained by Birds.

The Alamo and the Fall of Feathers

A century later came the Alamo.

The city had grown, though the bird population still outnumbered humans ten to one. When the battle began, both sides assumed the canaries would flee. They didn’t.

As cannonballs ripped through the mission walls, the canaries took up defensive positions in the rafters, shrieking battle hymns that were equal parts patriotic and revolutionary. Some claimed they pecked at enemy gunpowder; others swore they formed themselves into the shape of the Virgin Mary just before dawn on the final day.

In truth, the canaries were simply confused. War made no sense to them. Neither did bravery, or Texas independence, or why everyone shouted “Remember the Alamo!” when no one remembered to feed the birds.

After the battle, survivors reported hearing faint chirps in the ruins. Historians called it superstition—until one found a perfect yellow feather pressed into a fallen soldier’s diary. It read simply: Still chirping.

Modern Times

Centuries rolled on. Railroads came. Streets were paved. Air-conditioning was invented and immediately overworked. Yet the canaries endured, woven into the fabric of San Antonio like the faint smell of tacos after Fiesta.

By the 20th century, the city was a tourist paradise. People came for the River Walk, the margaritas, and the rumor that the 1731 “Sacred Protection Act” still shielded any bird with a decent singing voice from eviction. Tour guides told visitors to listen at night, when the canaries held their own secret parades over the water.

Then came basketball.

When San Antonio earned an NBA franchise, fierce debate erupted over the team’s name. Older residents lobbied for The Canaries, invoking the city’s chirping founders. They even drafted a mascot: a six-foot bird in a powdered wig named Señor Tweeto.

The younger crowd wanted something tougher—something that wouldn’t get eaten by the Lakers.

After months of argument, the city chose The Spurs, honoring cowboys, boots, and machismo over melody. The canaries were outraged. They staged a protest outside the arena, flapping in formation that spelled “FOWL PLAY.” One allegedly dive-bombed a Sports Illustrated reporter.

Peace was eventually restored. The Spurs won championships, the River Walk sparkled, and the birds kept singing.

Today, if you stroll through downtown San Antonio at sunrise, you might still hear them—the descendants of those original island settlers, chirping their opinions over the traffic and tourists. And if you listen closely enough, between the echoes of mariachis and basketball chants, you might swear you hear the faintest little refrain:

“Remember the Alamo… but don’t forget the canaries.”

Author’s Note:

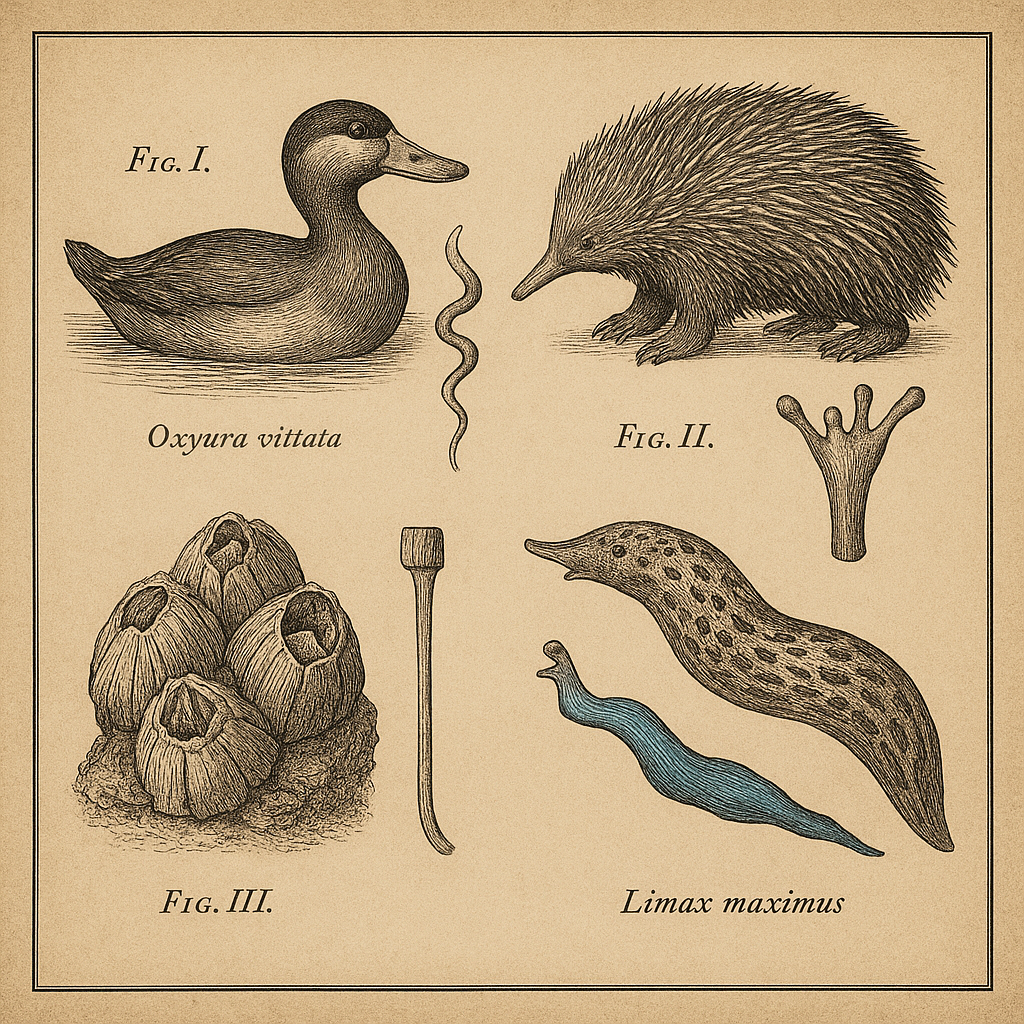

Every city has a founding myth. Rome had wolves, Athens had wisdom, and San Antonio—by some cosmic clerical error—had canaries.

As a responsible historian (or at least one who owns a decent hat), I’ve pieced together this account from royal decrees, mission records, and several questionable bird-related legends still whispered along the River Walk. Whether you believe it or not is your business.

Just remember: history isn’t always written by the victors. Sometimes it’s written by the loudest singers.