The First Annual Scribe Safari Strategic Planning Session (With Snacks)

By Mike

The barn smelled like a museum exhibit titled “Hay: A Retrospective,” with undertones of mouse urine, old leather, and the ghost of horse farts past. Dust motes drifted through the January light slanting in from windows so grimy they looked like they’d been installed specifically to make everything look melancholic and Midwestern. The conference table—a piece of salvaged oak that Mike had found behind a foreclosed furniture store—sat in the middle of the barn floor where a champion mare named Duchess had once stood, though she’d been dead for eleven years and wouldn’t have appreciated the irony.

Mike stood at the head of the table, wearing reading glasses he didn’t actually need but thought made him look more CEO-ish. His whiskers twitched with the gravity of the occasion.

“Thank you all for coming,” he said, which was stupid because they were contractually obligated to come, but Mike liked the sound of formality.

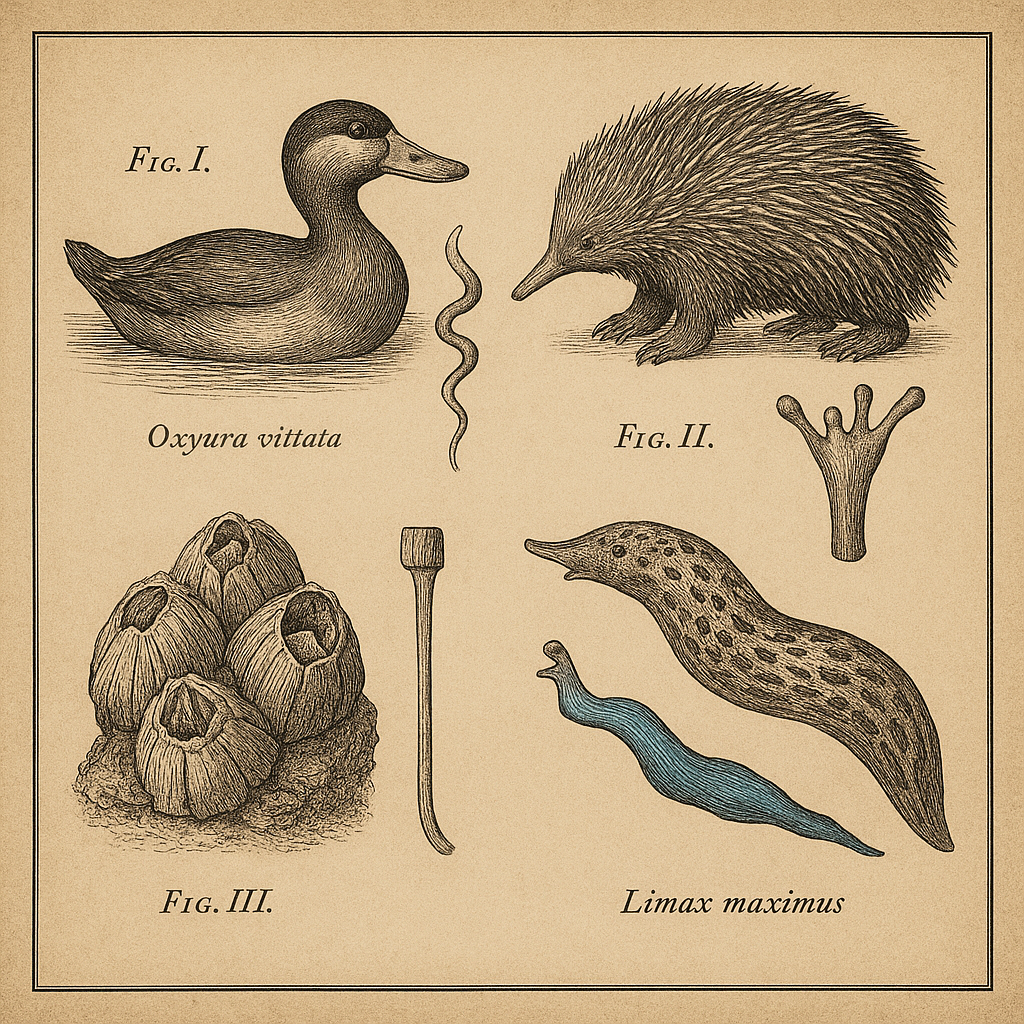

The correspondents filed in, their various gaits creating a percussion section of padding paws, clicking hooves, silent wing-beats, and the imperceptible whisper of something very small moving through the air. Bob the dog arrived first because dogs are pathologically incapable of being late to anything that might involve food. He stopped in the doorway, nostrils flaring like a furry vacuum cleaner that had just achieved consciousness.

“Is that… Salisbury steak?”

“Mrs. Mike went all out,” Mike said proudly.

Bob didn’t wait for permission, just dove face-first into the plate with the enthusiasm of someone who’d never heard of manners and wouldn’t care if he had. Gravy splattered onto the table. A small piece landed on a pie chart about Q4 readership metrics. Neither the steak nor the pie chart complained.

Maurice the goat clip-clopped in next, his rectangular pupils surveying the scene with the disdain of someone who’d seen some shit and wasn’t impressed by any of it anymore. His beard—which he definitely thought made him look distinguished—had bits of something questionable stuck in it. When he saw the stack of pancakes, he bleated once, a sound that conveyed both surprise and philosophical acceptance of the universe’s occasional generosity.

“Are these ethically sourced?” he asked, already moving toward them.

“They’re from Costco,” Mike said.

“That’s not an answer.” But Maurice was already eating them, syrup dripping down his chin into his beard, adding to the collection of questionable bits.

Penelope the owl swooped in through the open loft window with the silent precision of a feathered assassin. She landed on the back of an empty chair, her talons clicking once against the wood. Her enormous eyes—each one roughly the size of her brain, which she was very sensitive about—swiveled to focus on the plate of fried mouse.

The barn held its breath.

“Is that…” Penelope’s head rotated 180 degrees to look at Mike, because owls do that when they want to make you uncomfortable and it works every single time. “Is that Gerald?”

“I don’t think Mrs. Mike knew your neighbor personally,” Mike said carefully.

“Gerald had a distinctive musk. That’s Gerald.”

“I’m sure it’s just a random—”

“THAT’S GERALD.”

But even as she said it, Penelope was extending one talon toward the plate, because owls are fundamentally pragmatic about death and also because it smelled really, really good. She ate Gerald with the slow, deliberate precision of someone at a Michelin-starred restaurant who was also maybe having a mild existential crisis about the whole thing.

And Bernice. Bernice the fly. She was already there, had been there the whole time, because that’s what flies do—they arrive before you know they’ve arrived and they leave after you’ve forgotten they existed. She perched on the rim of the crystal dish that held a single sugar cube, her compound eyes taking in seventeen different perspectives of the same cube simultaneously, which was how she experienced most of existence: fractured, repetitive, and sweet when she could manage it.

When she saw the sugar cube—her sugar cube—her tiny wings vibrated with something that might have been joy or might have been the early stages of a sugar rush or might have been both because flies don’t really distinguish between emotions and metabolic processes.

She landed on the cube and began to eat in the only way flies can eat: by vomiting on it first. It was beautiful and disgusting at the same time, like most things in nature.

They ate in silence, except for Bob, who ate with the sound of a small wet avalanche, and Maurice, who ate while maintaining aggressive eye contact with everyone because goats are like that. The barn held the moment like a snow globe: dust, light, the smell of old wood and newer food, the sense that something important was happening even though they were just animals sitting in an abandoned building pretending they had jobs.

Mike cleared his throat. “Right. So. Let’s talk about where we’ve been.”

He pulled out a leather notebook that had “STRATEGIC INITIATIVES” embossed on the cover, which he’d gotten at a bankruptcy sale for a motivational speaking company. “Since April, we’ve published forty-seven stories. Penelope, your investigative piece on the vole trafficking ring in the north meadow was… thorough.”

Penelope’s head swiveled 270 degrees, which was unnecessary and vaguely threatening. “‘Thorough’ is criticism disguised as a compliment.”

“It was eight thousand words.”

“The subject demanded depth.”

“You included a three-page sidebar about the aerodynamics of silent flight and how it makes you superior to other birds.”

Penelope’s talons clicked against the chair. “Context is journalism.”

Mike moved on before she could demonstrate those talons on his face. “Bob, your exposé on the underground squirrel racing circuit was nominated for a Pawlitzer.”

Bob looked up from where he’d been licking the table. “Really?”

“No. But it could have been. If there was a Pawlitzer. And if anyone read past the first paragraph, which was just you describing how good the fire hydrant on Maple Street smells.”

Bob’s tail stopped wagging. The betrayal hit him like a rolled-up newspaper to the soul. He made a small wounded sound that was somehow both pitiful and accusatory, then went back to licking the table because emotional processing is hard and gravy is easy.

Maurice stopped mid-chew, a piece of pancake hanging from his beard. “My investigative series on the Corn Syndicate was hard-hitting journalism.”

“It was three stories about why you ate an entire cornfield and didn’t feel bad about it.”

“I extrapolated systemic concerns!”

“You called agriculture ‘a conspiracy against goats specifically.'”

Maurice lifted his head proudly, beard dripping with syrup and righteousness. “I stand by that. Everything is a conspiracy against goats. Fences. Gates. The concept of property ownership. Shoes.”

The barn seemed to lean in, the old wood creaking like it was taking notes. A spider in the corner stopped spinning to listen. Even the dust motes slowed down. On the sugar cube, Bernice paused her vomit-eating to pay attention.

“Bernice,” Mike said, his voice softening because even though she was just a fly, her work was legitimately beautiful, “your column ‘Scenes from the Wall’—the observations about what happens in this barn when no one thinks anyone’s watching—it’s… it’s really moving.”

Bernice’s wings buzzed once, a sound like a tiny violin playing a note of pure vulnerability.

“You mean it?” Her voice was so small Mike had to lean forward to hear it, and even then he wasn’t sure if he’d heard it or just felt it somehow.

“Yeah. People love it. It makes them cry in a good way. Like when they realize that every small thing is watching and remembering and that nothing is ever really forgotten, not even the ordinary moments, especially not those.”

Bernice lifted off the sugar cube and did a small loop in the air, which for flies is the equivalent of weeping openly. “I just write what I see. Which is everything. All the time. From every angle. It’s actually kind of exhausting.”

“Sounds like a disability,” Maurice muttered.

“Says the goat who ate a mailbox last week,” Penelope observed.

“It was leaning funny. It was basically asking for it.”

Mike banged his tiny paw on the table, which made no sound at all but everyone pretended to be called to order anyway. “Right! Moving forward. What are you all working on?”

Bob went first because he’d finished the Salisbury steak and had moved on to eating the plate and needed something to do with his mouth while he chewed ceramic. “I’m doing a story about why the mailman is the villain in society.”

“That’s just speculation based on personal grudges.”

“IT’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM. He comes to the house EVERY DAY. That’s not normal. No one else does that. It’s suspicious.”

Maurice cleared his throat with the self-importance of someone about to ruin the mood. “I’m working on a piece about the disappearance of Maurice Jr.”

The barn went silent. Even Bob stopped chewing the plate.

“Your kid?” Mike asked carefully.

“I believe he was taken by the Coyote Collective. I have… sources.” Maurice’s rectangular pupils went distant and hard. “I will find him. And I will headbutt everyone responsible.”

Nobody mentioned that Maurice Jr. had run away three months ago after calling his father “an insufferable narcissist who thinks eating garbage is a personality trait,” because Maurice didn’t need to hear that right now. Or ever.

“That’s… ambitious,” Mike said. “Penelope?”

“I’m writing an exposé on the hawk community. They think they own the sky. They think their diurnal hunting schedule makes them superior. I’m going to destroy them with facts.” Her eyes gleamed with the particular madness of someone who hunts at night and holds grudges forever.

“Bernice?”

The fly landed on Mike’s shoulder, which was either a gesture of intimacy or she was just tired. “I’m writing about what it means to have a lifespan of thirty days. To live in this barn and see seasons change in fast-forward. To watch everyone I’ve ever known die and be born and die again. To be the memory of a place that doesn’t remember itself.”

The weight of that landed like a bale of hay dropped from the loft. The barn seemed to contract around them, smaller and more fragile than before, just wood and nails and the knowledge that everything ends, even the remembering.

“Jesus, Bernice,” Penelope whispered.

“Sorry. It’s been a weird January. Also I might be dying. It’s hard to tell. Every day feels like dying when you’re a fly.”

Mike rallied because that’s what editors do when things get too real and also too existentially horrifying. “Okay! Last agenda item. Should we hire someone new? Another reporter?”

“YES,” Bob barked immediately because dogs love new friends.

“Absolutely not,” said Penelope, because owls hate change.

“Only if they’re ruminants,” Maurice added, because goats have very specific prejudices.

Bernice just buzzed, which could have meant anything or nothing because she was literally vibrating at 200 beats per second and consciousness was probably negotiable at that frequency.

“What kind of animal?” Maurice asked suspiciously.

“I was thinking maybe—”

The barn door exploded inward. Not opened. Exploded. Like it had been kicked by something with deep-seated anger management issues and a vendetta against hinges.

In the doorway stood a beaver.

He was wearing a tiny fedora with a press card tucked in the band. He had a cigarette behind one ear and a notebook clutched in his weird little hand-paws. His front teeth could’ve been classified as weapons in several states, and probably were.

“Name’s Garrett,” he said in a voice that sounded like gravel gargling whiskey. “Heard you might need someone who knows how to build a goddamn story. And also dams. But mostly stories.”

Everyone stared.

Bob’s tail started wagging uncertainly because dogs are fundamentally optimistic about violence.

Penelope’s head rotated completely around twice, which was owl for “what the actual fuck.”

Maurice squared up, lowering his head in a way that suggested imminent headbutting.

Bernice flew up to the rafters because self-preservation is the first rule of journalism.

“Also,” Garrett continued, pulling out a business card that said GARRETT MCBEAVERSON, INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALIST & DAM SPECIALIST, “I got a tip that someone in this operation has been embezzling snack funds. And I’m gonna find out who.”

Bob stopped mid-wag, eyes wide, gravy still on his face, the remains of what might have been an expense-account Salisbury steak suddenly feeling very incriminating. Also he’d eaten the plate. That probably wasn’t covered by the snack budget.

Maurice’s pupils narrowed to slits. “I don’t like your tone.”

“I don’t like your beard. We all got problems.”

Mike looked at Mrs. Mike through the barn window, where she was watching with her arms crossed and a knowing smile. He looked at his team: a dog covered in gravy and guilt, an owl planning murder, a goat ready to commit assault, and a fly having an existential crisis in the rafters.

The barn held its breath, dust frozen in the light, the smell of old wood and the future hanging in the air like a question nobody wanted to answer.

“Well,” Mike said slowly, “I guess we should talk about your sample work.”

Garrett grinned with every terrifying tooth visible.

“Oh,” he said, pulling out a rolled-up newspaper. “We’re gonna do more than talk.”

He threw the newspaper on the table. The headline read: “LOCAL MOUSE EMBEZZLES CHEESE: A FIVE-PART INVESTIGATION.”

Mike’s whiskers went rigid.

Somewhere in the loft, a mouse who’d been listening to everything—and who was definitely not Gerald because Gerald was currently being digested by an owl—suddenly reconsidered her career choices and started updating her resume.

Bob ate the newspaper because it was there and he had a problem.