Millard Fillmore and the Velvet Rope of History (Presidents’ Day Edition)

By Mike

No one remembers Millard Fillmore.

This is not an insult.

It is a weather report.

If history were a nightclub, Millard Fillmore would be the guy holding a perfectly valid ticket while being gently escorted toward the alley by a bouncer named Destiny.

“Nothing personal,” Destiny would say. “You just don’t have… branding.”

Somewhere behind the velvet rope, Lincoln is telling jokes.

Jefferson is flirting with a chandelier.

Washington is doing slow-motion hero poses in a powdered wig.

And Fillmore is standing outside with Chester A. Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and a slightly confused Franklin Pierce, comparing notes on obscurity.

They call themselves The Committee for Presidents You Forgot Existed.

They meet in a drafty hallway just off the main corridor of American Memory, beneath a flickering EXIT sign that hasn’t worked since 1897.

Their headquarters is furnished with folding chairs, a chipped coffee urn, and a portrait of James Buchanan that nobody can quite explain.

The portrait just showed up one day.

Like mold.

Or regret.

Millard Fillmore, former Commander-in-Chief and current Patron Saint of Historical Shrugs, serves as chairman.

He clears his throat with the authority of a man who once vetoed legislation and now struggles to order at Starbucks.

“Gentlemen,” he says, “we are not failures.”

Pause.

“We are… footnotes.”

This does not inspire applause.

Chester Arthur adjusts his sideburns, which he keeps immaculate out of spite.

“I had magnificent facial hair,” Arthur says. “That should count for something.”

“It counts,” Fillmore says gently. “In barber museums.”

Benjamin Harrison sighs.

“My grandfather gets all the attention. He chopped down one tree and stole my entire career.”

Franklin Pierce stares into his paper cup like it contains the answer to life.

“It was cold,” he murmurs. “Everything was cold.”

No one asks what he means.

They have learned not to.

Outside, history thunders past like a parade of fire trucks and marching bands.

Roosevelts riding bears.

Kennedy smiling in black and white.

Lincoln splitting darkness with words.

And here, in the hallway, stand the men who governed competently enough to be invisible.

They were presidents in beige.

Leaders in khaki.

Commanders-in-Chief of Meh.

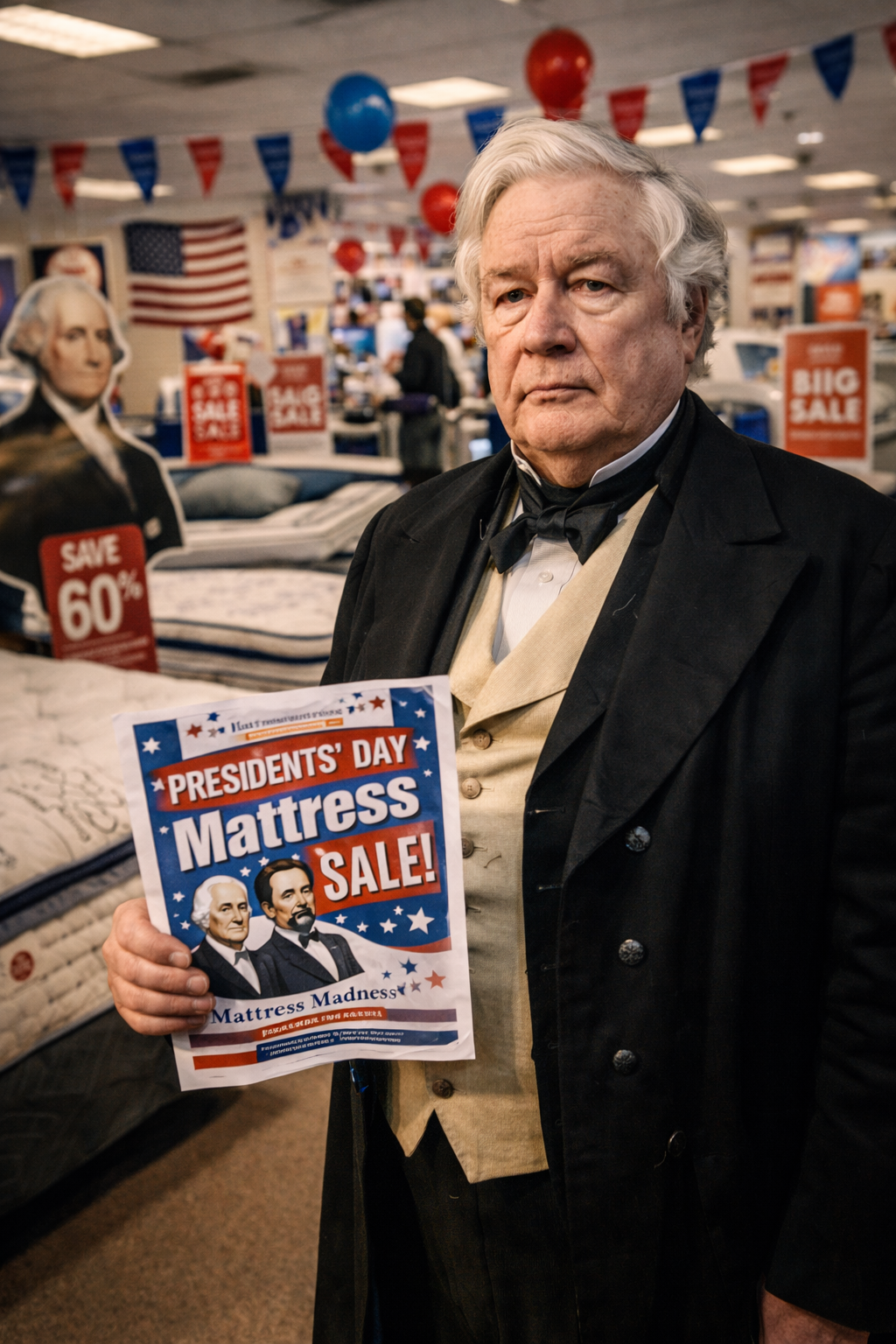

Then comes Presidents’ Day.

Once a year, America pretends to remember all of them.

Retailers drape themselves in patriotic bunting and declare that nothing honors the executive branch like thirty percent off recliners.

Car dealerships unleash bald eagles in their commercials.

Mattress stores claim Washington personally endorsed memory foam.

And somewhere in this commercial thunderstorm, Millard Fillmore waits.

Surely, he thinks.

This is my moment.

But Presidents’ Day is really Lincoln-and-Washington-and-Occasionally-Somebody-Else Day.

It is a holiday where the guest list says “All Presidents Welcome,” but the bouncer only recognizes two faces.

Fillmore once tried attending.

He wore his best nineteenth-century coat.

He brought a pamphlet.

It read: “I Was Also Here.”

Security asked him to move along.

“Private event,” they said.

“Sir, this is for legends.”

Back in the hallway, the Committee gathers around a television.

They watch Presidents’ Day coverage.

There is a wreath.

There is a reenactor.

There is a child mispronouncing “Emancipation.”

No one mentions Millard.

No one mentions Chester.

No one mentions Benjamin.

The coffee grows colder.

James Buchanan’s portrait smirks.

Fillmore, for the record, was not a bad president.

This is the problem.

Bad gets remembered.

Great gets canonized.

Average gets erased.

He passed laws.

Balanced things.

Managed crises with the emotional temperature of lukewarm oatmeal.

History prefers fireworks.

Fillmore offered simmer.

Sometimes he wonders what he should have done differently.

Started a war?

Worn a cape?

Adopted a scandalous mistress named Velvet Magnolia?

Too late now.

Once a year, after Presidents’ Day ends and the banners come down, they hold the Forgotten Presidents’ Ball.

Attendance: sparse.

Entertainment: a harpsichord playlist and a PowerPoint titled

“Moments When We Almost Mattered.”

Fillmore gives the keynote.

“Friends,” he says, “today America celebrated two men. Tomorrow it will forget thirty-eight more.”

This gets a small, respectful nod.

“Still,” he continues, “we showed up. We signed things. We tried.”

“And in a republic,” he adds softly, “trying counts.”

Outside, tourists shuffle through Mount Rushmore gift shops.

They buy Lincoln mugs.

They buy Washington socks.

No one buys Fillmore anything.

Not even accidentally.

Yet sometimes — late at night, after Presidents’ Day sales end and history exhales — a janitor pauses in front of a forgotten portrait.

He squints.

“Who was that guy?”

And for half a second,

Millard Fillmore exists again.

Which, in the end, is all history ever promises