The 525-Pound Tuna and Other Expensive Ways to Say “Look at Me”

By Penelope the Owl

I have lived long enough to see men pay ruinous sums for houses, horses, paintings, spouses, and now—apparently—a very large fish. The latest object of conspicuous devotion is a 525-pound bluefin tuna, recently auctioned for a price so lavish it ought to have come with a fainting couch and a priest.

The tuna, I regret to report, did not attend the auction in person. It lay elsewhere, dead and compliant, while men in clean shoes and confident voices transformed it into a headline. One imagines it would have blushed, had it the blood pressure.

This is not a purchase made for hunger. No one spends that much money because they are peckish. This is a transaction rooted in the ancient and honorable tradition of masculine display—the same instinct that once inspired pyramids, duels, and sports cars shaped like regret.

The New Year tuna auction, for the uninitiated, is not about eating. It is about ceremony. The fish is wheeled out like royalty, admired from all sides, and mentally converted into social currency. Cameras flash. Hands are shaken. Someone makes a joke that falls flat but is laughed at anyway because it cost several million dollars to be there.

Later, the buyer will say he did it “for tradition.” This is the same explanation men offer for hats they should not wear and opinions they should not voice.

The tragedy—or comedy, depending on your temperament—is that the eating itself is rather beside the point. Bluefin tuna, when properly prepared, is very good. It is also very fatty, very rich, and very capable of inspiring murmured compliments from people who enjoy murmuring. But it does not sing, glow, or whisper secrets of the universe. It tastes like tuna that has been thoroughly flattered.

Most diners will swear they can tell the difference. They cannot. What they are tasting is the knowledge that someone else paid too much for their pleasure. This is a powerful seasoning.

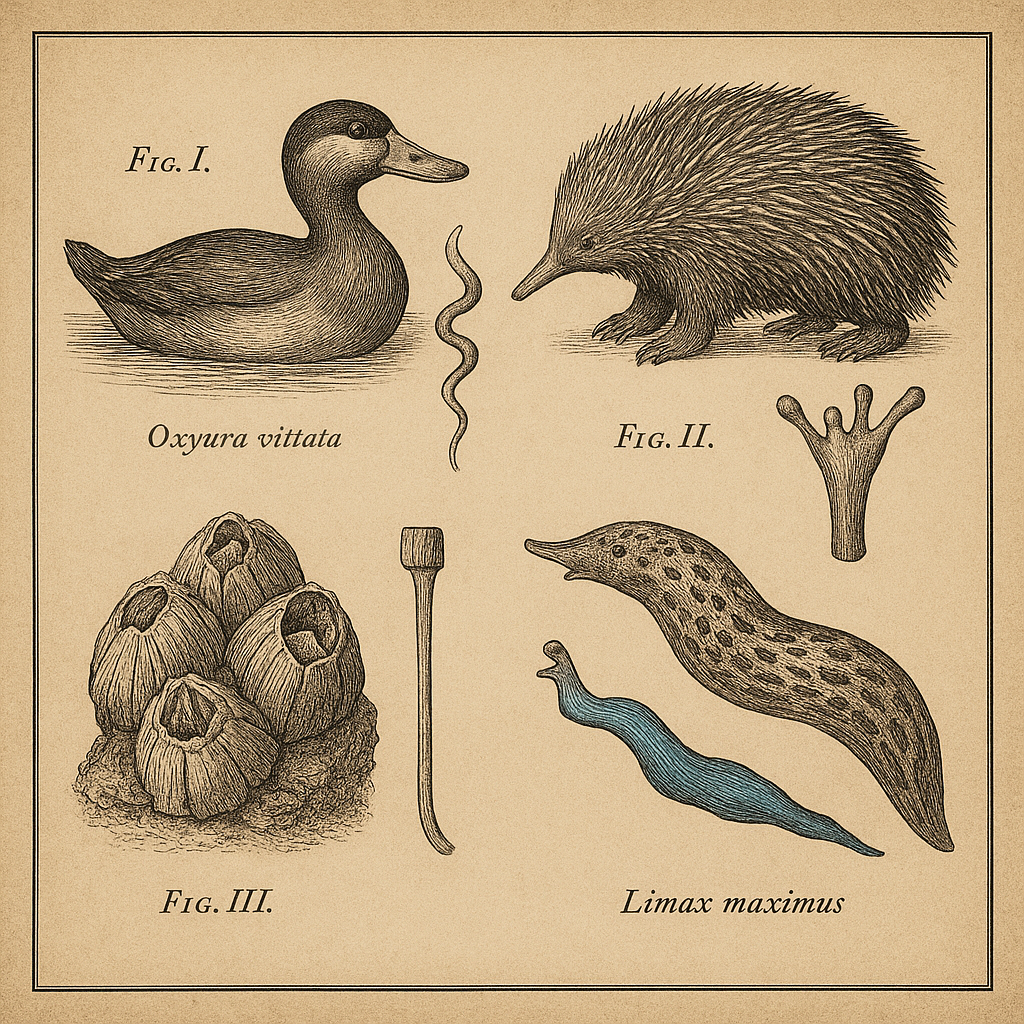

Meanwhile, marine biologists continue their lonely vigil, pointing out—gently, as one does to the very wealthy—that bluefin tuna populations have been pushed to the edge by decades of overfishing and prestige consumption. These warnings land with all the force of a fortune cookie. Concern is expressed. Nods are exchanged. The auction proceeds.

The fish itself, magnificent and migratory, once crossed entire oceans with purpose and speed. It outran predators, survived storms, and followed instincts older than the people who now photograph it. Its reward is to be sliced ceremonially while someone explains, at length, why this price was actually quite reasonable.

I do not begrudge the tuna its fame. If one must be eaten, one might as well be celebrated. But there is something exquisitely human about turning a living marvel into a competitive sport. We cannot simply admire. We must outbid.

The buyer’s name will linger long after the fish is gone. It will be mentioned at dinners and conferences and, one suspects, on golf courses. The tuna’s name—if it ever had one—will not. This is as it should be. History remembers the checkbook.

Next year, there will be another tuna. It will be larger, more expensive, and declared unprecedented, as though we had never overdone anything before. The men will gather again, the cameras will flash, and someone will say, “This one’s special.”

They always are.

Somewhere in the sea, a sensible fish will remain small, unnoticed, and alive. One can’t help admiring its restraint.